Peter Collinson (film director)

Peter Collinson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Peter Kenneth Collinson 1 April 1936 Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire, United Kingdom |

| Died | 16 December 1980 (aged 44) Los Angeles, United States |

| Years active | 1961–1980 |

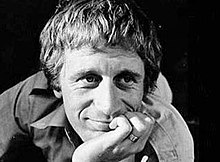

Peter Collinson (1 April 1936 – 16 December 1980) was a British film director probably best remembered for directing The Italian Job (1969).

Early life

[edit]Peter Collinson was born in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire in 1936. His parents, an actress and a musician, separated when he was two years old; he was raised by his grandparents. From the age of eight until 14 he attended the Actor's Orphanage in Chertsey, Surrey, where he had the chance to write and act in many plays.

Noël Coward, who was president of the orphanage at the time, became his godfather and helped him to obtain jobs in the entertainment industry, which was dramatized in the radio play Mr Bridger's Orphan by Marcy Kahan in 2013.[1] (Collinson later directed Coward in his best-known film, The Italian Job (1969)). He auditioned for RADA but was rejected, so went to work for the New Cross Empire theatre when aged 14. He did a variety of theatrical jobs until 1954, when he was called up for national service. He served as a private with the Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) for two years in Malaya during the Malayan Emergency.[2]

Career

[edit]Collinson's early television work included time as a floor manager for the BBC and directing for ATV at Elstree studios. He was an assistant director on a short, The Pit (1962), and made a documentary, Blackwater Holiday (1963).

He also worked with Telefís Éireann, the Republic of Ireland's national TV station, and in 1963 he won a Jacob's Award for his production The Bomb.[3][4] He produced a stage musical in Dublin, Carrie (1963), starring Ray McAnally.[5]

Collinson began to direct TV: the film Don't Ever Talk to Clocks (1964), In Loving Memory (1964), The One Nighters.[6] He also made episodes of Sergeant Cork (1964), The Sullavan Brothers (1964), The Plane Makers (1964), Love Story (1964–65), Front Page Story (1965), Knock on Any Door (1965), A Day of Peace (1965) Blackmail (1965–66), and The Power Game, Women, Women, Women and The Informer (all 1966).

Features

[edit]Whilst working in TV he met producer Michael Klinger, who offered him the director role on the film The Penthouse (1967); this became Collinson's directorial debut. Starring Suzy Kendall, the low-budget film was released in the US and proved to be a surprise hit.[7] Collinson followed it with Up the Junction (1968), starring Kendall and Dennis Waterman, which received some strong reviews.[8]

Collinson directed two films for Paramount, both produced by Michael Deeley: The Long Day's Dying (1968), a low-budget war film, and The Italian Job (1969), a caper movie starring Michael Caine and Noël Coward. Dino De Laurentiis said he was to direct a film about Ned Kelly in Australia, The Iron Outlaw, but it was never made.[9] Instead, Collinson went to Turkey where he directed Tony Curtis and Charles Bronson in You Can't Win 'Em All (1970). He clashed with Curtis during filming.[10] He was meant to helm a biopic of Robert Capa, but it was never made.[11]

Back in England he made Fright (1971), a thriller with Susan George. He did a horror movie for Hammer Films, Straight On till Morning (1972), with Rita Tushingham, then Innocent Bystanders (1972), a thriller shot in Spain and Turkey with Stanley Baker.

Collinson went to Spain to direct a Western, The Man Called Noon (1973).[12] He followed it with Open Season (1974), starring Peter Fonda; a remake of And Then There Were None (1974), filmed in Iran with Oliver Reed; a remake of The Spiral Staircase (1975), shot in England with Jacqueline Bisset; Target of an Assassin (1976), filmed in South Africa with Anthony Quinn; and The Sell Out (1976), shot in Israel with Reed.[13]

He went to Canada for Tomorrow Never Comes (1978), with Oliver Reed and Susan George; it was entered into the 11th Moscow International Film Festival.[14] He followed it with The House on Garibaldi Street (1979), a US telemovie starring Topol.

His last feature was The Earthling (1980), shot in Australia with William Holden and Ricky Schroder.[15][16]

He was meant to direct The Gangster Chronicles for US television but died shortly before filming was to begin. Richard Sarafian stepped in.[17]

Death

[edit]During the filming of The Earthling (1980), Collinson discovered he was terminally ill; he died from lung cancer in Los Angeles. He was survived by his wife Hazel and two sons.[18]

Filmography

[edit]- The Penthouse (1967)

- Up the Junction (1968)

- The Long Day's Dying (1968)

- The Italian Job (1969)

- You Can't Win 'Em All (1970)

- Fright (1971)

- Straight On till Morning (1972)

- Innocent Bystanders (1972)

- The Man Called Noon (1973)

- Open Season (1974)

- And Then There Were None (1974)

- The Spiral Staircase (1975)

- Target of an Assassin aka Tigers Don't Cry (1976)

- The Sell Out (1976)

- Tomorrow Never Comes (1978)

- The House on Garibaldi Street (1979)

- The Earthling (1980)

References

[edit]- ^ "Afternoon Play – Mr Bridger's Orphan". BBC.

- ^ "BRIEFING/WHO & WHY: "Plain hunt of an actor"". The Observer. London (UK). 14 November 1965. p. 23.

- ^ The Irish Times, 4 December 1963. "Presentation of television awards and citations".

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Death of film director". The Irish Times. 20 December 1980. p. 7.

- ^ "FESTIVAL PLAYS WELL BOOKED-EXCEPT ONE". The Irish Times. 27 September 1963. p. 4.

- ^ "COLLINSON REPLACED AS FESTIVAL DIRECTOR". The Irish Times. 4 August 1964. p. 1.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1968". Variety. 8 January 1969. p. 15. Please note this figure is a rental accruing to distributors.

- ^ A.H. WEILER (8 October 1967). "And Now Antonioni Will 'Blow Up' America". The New York Times. p. X19.

- ^ "DINO DE LAURENTIIS SETS NED KELLY FILM". Los Angeles Times. 23 May 1969. p. e13.

- ^ "Tony Curtis Ends Turkey Filming". Los Angeles Times. 5 November 1969. p. f15.

- ^ A.H. WEILER (12 April 1970). "A Kooky Time for Coco: Kooky Coco". The New York Times. p. D13.

- ^ Johnson, Molly. (22 October 1972). ""Englishman Puts on His Chaps"". Los Angeles Times. p. m22.

- ^ "Obituary 2 -- No Title". Chicago Tribune. 20 December 1980. p. w_a10.

- ^ "11th Moscow International Film Festival (1979)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Patricia (20 January 1980). "AN AUSSIE WELCOME FOR 'EARTHLING'". Los Angeles Times. p. n24.

- ^ ""THE EARTHLING"". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 47, no. 24. 14 November 1979. p. 19. Retrieved 27 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (22 February 1981). "TV VIEW: 'The Gangster Chronicles'--A Flashy Portrait of Some Unpretty People". The New York Times. p. D29.

- ^ "OBITUARY: British film and TV director". The Guardian. 20 December 1980. p. 2.

Other sources

[edit]- Field M. (2001). The Making of the Italian Job. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-8682-1.

External links

[edit]- Peter Collinson at IMDb

- Peter Collinson biography and filmography at the BFI's Screenonline

- Collinson interview Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine